Like so many others, my organization over the last few years has been leveraging AWS cloud services for IT infrastructure. It started out with one account, one VPC, one VPN tunnel (2 for redundancy) and a handful of EC2 instances. Gradually over time this simple cloud presence has multiplied drastically. There are now numerous EC2 instances, VPCs, VPN tunnels, regions in use, and AWS accounts. I was not around to witness this AWS footprint grow; I inherited the network responsibilities after the fact.

When arrived I investigated the on premises to AWS connectivity and discovered the web of data center to VPC VPN tunnel networking. Setting up internal connectivity from an on prem router/firewall to a VPC is relatively straight forward. In AWS you follow the steps here to setup a site to site IPSEC tunnel and then download a configuration ‘walk through’ to configure your physical device where you want connectivity. Each VPN tunnel you configure on the AWS side results in two tunnels to your on prem gateway for redundancy. In the end on the customer network side you get two VPN tunnels to every VPC needing internal network connectivity. As one can imagine this doesn’t scale very well. Even 15 AWS VPCs results in 30 VPN tunnels with 30 separate BGP peers or static routes depending on which option you go for in terms of routing.

I was able to simplify my org’s cloud networking by utilizing AWS’ Transit Gateway service. A Transit Gateway (TGW) essentially moves your cloud networking architecture to a hub and spoke model. Instead of setting up direct connections from your data center to each VPC separately, each VPC is connected to the TGW and the local router/firewall has an IPSEC VPN tunnel only connecting to the TGW as well. The TGW allows for all internal connectivity between VPCs and on prem. Per the example above, moving to a TGW hub and spoke you would go from 30 VPN tunnels to two. The two VPN tunnels to the TGW are for redundancy and equal cost multi-path if you want to go the ECMP route.

Example Before:

Example After:

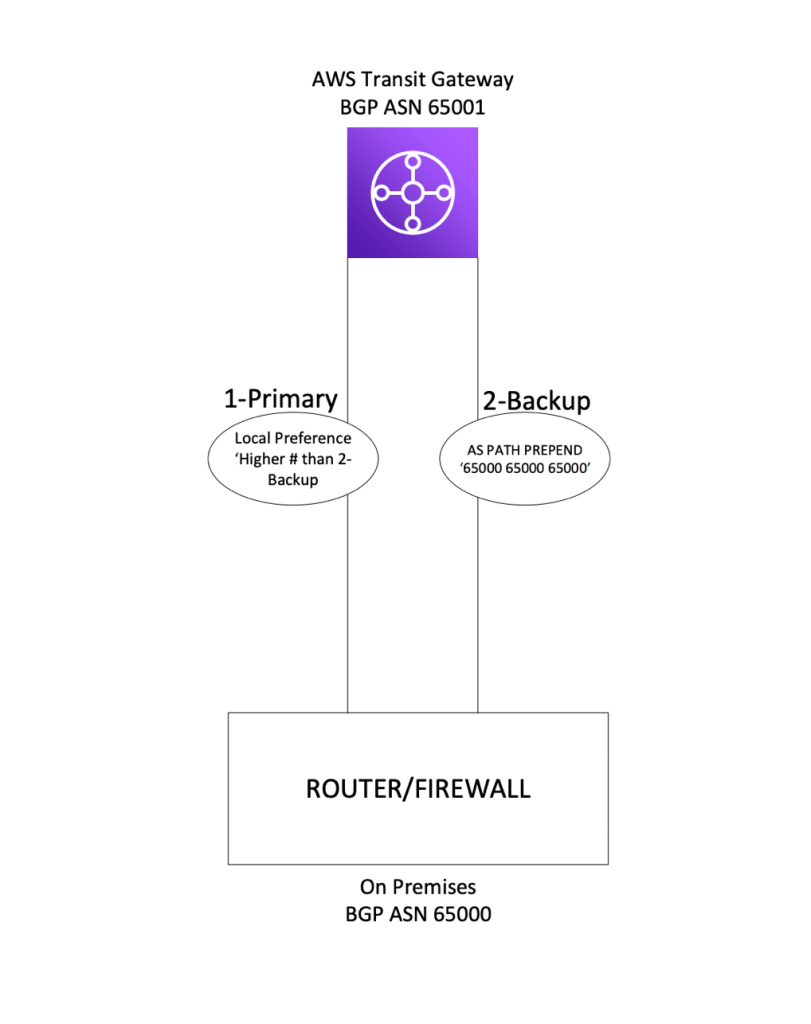

Per the AWS Transit Gateway documentation, the maximum bandwidth per VPN connection is 1.25 Gbps which exceeds the bandwidth of the internet connection the org is using to terminate the site to site tunnel. This means ECMP is not needed and an active/passive tunnel approach is more suitable. An issue I ran into while setting this up had to do with tunnel priority and BGP. I discovered that when setting up a standard VPN tunnel direct to VPC, AWS will advertise routes to an on prem device over BGP with a MED value of 200 for one tunnel and 100 for the other. This allows for a primary and secondary tunnel, avoiding asymmetric routing, etc. However, when two tunnels are configured to a TGW AWS does not advertise routes to a customer on prem device with different MED values. This obviously is an issue if you’re looking for an active/passive approach with zero ECMP.

After digging around AWS documentation and the internet I discovered that BGP peering to a TGW will in fact honor AS Path Prepend. As a result I was able to use AS Path Prepend on the routes advertised over the secondary tunnel, and Local Preference on the routes advertised to our on prem device from AWS over the primary tunnel.

I believe these same BGP attributes can be used for AWS DirectConnect customers as well.

For some reason I struggle to find proper AWS documentation and setting this up took longer than it needed to. I hope this will save someone some time if they run into this same situation.